Voter ID and Judge Richard Posner

I just read (via Eric) the Salon article “GOP voter ID law gets crushed: Why Judge Richard Posner’s new opinion is so amazing,” which beckoned me to go on and read the dissent in full. I did, and it was indeed entertaining. Also see Posner on HuffPost Live.

For the record, absent any evidence of a substantial (or any) problem with the existing voting requirements laws, I think time spent on this issue is a complete waste of resources that could be spent reforming our election system in general. We could start with:

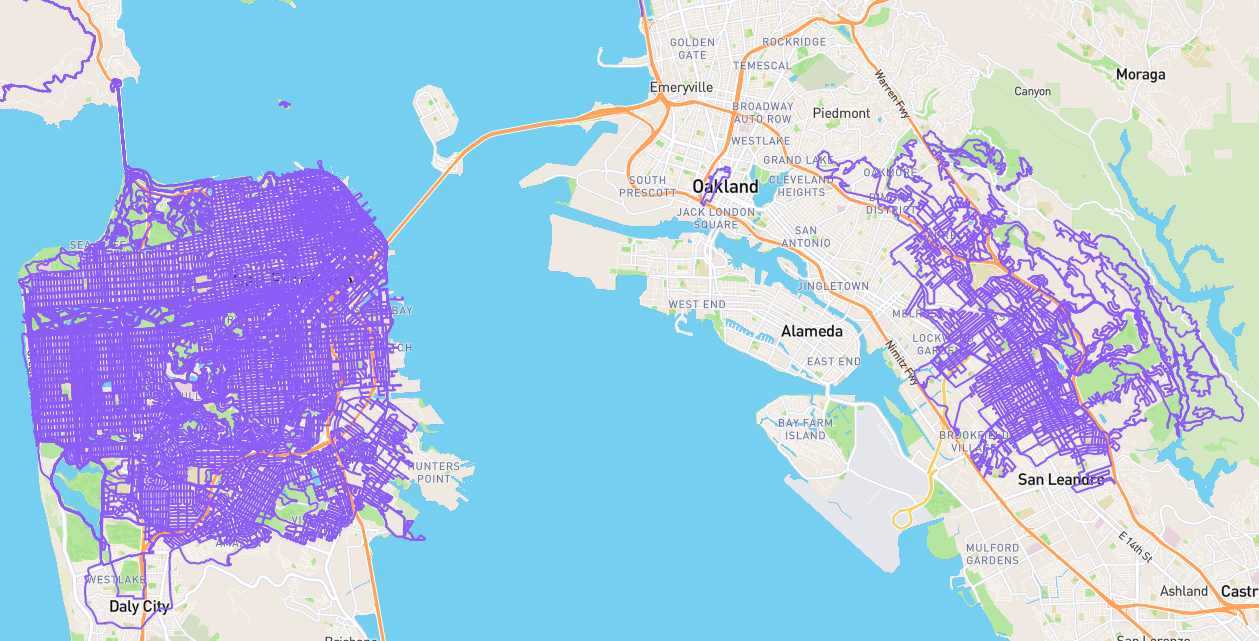

- splitline districts, so “there is one and only one drawing possible [and] you know the maps are going to be completely unbiased.”

- range voting to both eliminate the two party system and even encourage members of the same party to run simultaneously.

And for my future reference, some of the gems from Posner’s dissent:

Even Fox News, whose passion for conservative causes has never been questioned, acknowledges “Voter ID Laws Target Rarely Occurring Voter Fraud,” noting “even supporters of the new photo ID laws are hard pressed to come up with cases in which someone tried to vote under a false identify.”

The panel opinion does not discuss the cost of obtaining a photo ID. It assumes the cost is negligible. That’s an easy assumption for federal judges to make, since we are given photo IDs by court security free of charge. And we have upper-middle-class salaries. Not everyone is so fortunate. It’s been found that “the expenses … typically range from about $75 to $175. … Even when adjusted for inflation, these figures represent substantially greater costs than the $1.50 poll tax outlawed by the 24th amendment in 1964.”

The panel opinion suggests that obtaining a photo ID to vote can’t be a big deal, because one needs a photo ID to fly. That’s a common misconception. Since, despite the 9/11 attacks that killed thousands, a photo ID is not considered essential to airline safety, it seems beyond odd that it should be considered essential to electoral validity.

The panel piles error on error by stating that “photo ID is essential [not only] to board an airplane … [but also to] pick up a prescription at a pharmacy, open a bank account…, , buy a gun, or enter a courthouse to serve as a juror or watch the argument of this appeal.” In 35 states, including Wisconsin, you don’t need a photo ID to pick up all prescriptions. Bank customers do not need a photo ID to open a bank account. Federal law does not require a photo ID to purchase firearms at gun shows, flea markets, or online. It’s true that our courthouse requires a photo ID to enter, but the Supreme Court requires no identification at all of visitors.

The panel does say, in the same paragraph of its opinion, that it “accept[s] the district court’s finding [that 300,000 registered voters lack acceptable photo ID in Wisconsin] in this case,” but coming after a recitation that mistakenly implies that one can do virtually nothing in this society without a photo ID, the implication is that those 300,000 have only themselves to blame for not being allowed to vote.

The panel opinion dismisses the Absolabehere and Persily article on the ground that because it was published in the Harvard Law Review, it was not peer-reviewed. So much for law reviews. (And what about Supreme Court opinions? They’re not peer-reviewed either.)

A glance back at Table 1 will reveal that 12 states do not require a photo ID or any strict non-photo substitute. If Wisconsin’s deterrence rationale is sound, we should expect voter-impersonation fraud to be common in those states. Wisconsin does not argue that, and we know of no evidence that it could produce in support of such an argument. Nor does it argue that there is something special about Wisconsin—some unusual compulsion to engage in voter-impersonation fraud in the absence of strict photo ID requirements—that would make the experience in the 12 non-strict non-photo ID states irrelevant to the likely effect of the Wisconsin law in deterring (or rather not deterring) voter-impersonation fraud.

There was a section on “legislative facts”:

As there is no evidence that voter impersonation fraud is a problem, how can the fact that a legislature says it’s a problem turn it into one? If the Wisconsin legislature says witches are a problem, shall Wisconsin courts be permitted to conduct witch trials?

We learned (if we didn’t already know) at the time of Bush v. Gore that every locality in the country conducts elections in its own way—voting machines, paper ballots, computer punchcards, whatever—a situation unsuited to the application of the concept of legislative fact.

Does the Supreme Court really want the lower courts to throw a cloak of infallibility around its factual errors of yore? Shall it be said of judges as it was said of the Bourbon kings of France that they learned nothing and forgot nothing?

And then more on the burden, and how the lower court decision was full of errors:

The author of this dissenting opinion has never seen his birth certificate and does not know how he would go about “scrounging” it up. Nor does he enjoy waiting in line at motor vehicle bureaus. There is only one motivation for imposing burdens on voting that are ostensibly designed to discourage voter(impersonation fraud, if there is no actual danger of such fraud, and that is to discourage voting by persons likely to vote against the party responsible for imposing the burdens.

The panel opinion bolsters its suggestion that “scrounging” up a birth certificate is no big deal by stating that six voter witnesses in the district court “did not testify that they had tried to get [a copy of their birth certificate], let alone that they had tried but failed.” That’s another error by the panel, for five of these witnesses testified that they had tried, but had failed, to obtain a copy of their birth certificate in order to be able to obtain a photo ID to be able to vote, and the sixth (who died shortly before the trial) had repeatedly but unsuccessfully tried to obtain a copy of her birth certificate.

Any reader of this opinion who remains unconvinced that scrounging for one’s birth certificate can be an ordeal is referred to the Appendix at the end of this opinion for disillusionment.