Emotional expectations of personal genomics

I started reading a book Yizhen left on my shelf after he headed back to Chicago to begin his second year at Biocode: The New Age of Genomics, by Dawn Field and Neil Davies, is kind of an overview of the state of biotechnology. I apologize in advance to anyone reading this; I just wanted to make a quick comment about the emotional distress warnings for a Stanford class, but this turned into another train of thought whose course was less direct than anticipated and whose destination was so vague the conductor isn’t even sure if we are there yet.

So far the book has been somewhat interesting. Most of the concepts aren’t new to me — these are the moments I live for, making me proud to have spent five years of me life earning a degree in biochemistry — but it’s good to read about some of the events in the industry and some of the background stories. Technology is progressing faster and faster as we approach the singularity, so even though I graduated just five years ago, sometimes I feel like I know nothing about my field.

Anyway, this was just supposed to be a quick note of an entry, so I don’t want to get too sidetracked. I just want to mention so far the flow of the book has been slightly disjointed, or at least not smoothly transitioned. It seems more like a smattering of facts and small stories thrown together than a story. But then again that impression might just be due to reading it in small chunks.

What I really wanted to comment about was a specific passage from the second chapter on personal genomics. The authors gave an overview of the Personal Genome Project run by Harvard’s George Church, as well as the popular consumer genotyping company 23andMe. For those who don’t know, one is a university run research project and the other a commercial enterprise, but they both offer DNA sequencing for public and personal benefit.

With 23andMe, there is less of a privacy concern unless you are extremely fearful the company might violate trust and do something insidious with your genetic data. 23andMe is basically just for personal trait information and perhaps some pooled genetic studies within the company. The Personal Genomic Project is quite different in that it explicitly aims to make public the entire DNA sequence of study participants. Despite or because of PGP’s somewhat radical philosophy, they are also extremely cautious with enrolling. They go so far as to warn participants they might discover they have a serious disease, their parents might not be their parents, or their DNA could be used by anyone in the world to do such nefarious things as planting your DNA at the scene of a crime to wrongly implicate you for murder. Of course, there are many benefits, not the least of which is better understanding what makes us us. And regarding that worst case scenario, I read an unspoken converse: having your DNA in a public database could serve as your defense if you are charged for murder on the basis of your DNA being found at the crime scene.

Especially as we’ve transitioned from an in person, small business type economy to one that is heavily Internet based and often impersonal, people seem hyper concerned about privacy across the board, not just in regard to biological data. This may be for good reason, as there have been many high profile financial “data leaks” lately. (And not leaks in the sense an insider gave away information for public benefit.) Though I would argue those are problems with the banking system, and by using them as our excuse to close ourselves and hide any information about us from our neighbors, we are letting the terrorists win.

In any case, there are clearly whole sections of life that the youngest generations have no qualms about making public, as Facebook and friends have proven. But there seems to be a big difference between content shared with a social circle “privately” and content searchable by Google. I have dealt firsthand with requests to remove information about dozens or hundreds of people, both when I worked at The Badger Herald and also in regard to my personal website. People are very concerned about what can be found out about them on Google. Everything from politics to parties can be incriminating or embarrassing. The most common pretense for wanting the stuff hidden has been the prospect of finding new employment.

I became a 23andMe user after my mom got me one of their kits for Christmas 2011. I thought it was cool, and immediately sent my saliva off to the lab. I didn’t spend much time researching the company or worrying about privacy concerns, but I am also perhaps an outlier. I have been blogging for a while and generally don’t worry about incriminating things being found on the Internet. I like to joke even if I run for president, I don’t care that people might find information that simply proves I am human. We don’t need proof that we’ve all got junk!

So back to the book, pages 28 and 29 gave an overview of the Stanford class “Genomics 210: Genomics and Personalized Medicine” started by Stuart Kim. The book explains the apparently extensive attention given to possible sensitivity to the course content, which builds on a personal genomic profile done by 23andMe.

Stanford is careful about managing emotional expectations about the results that will be returned. They can be unsettling. Testing is confidential and voluntary. Students must attend informed consent sessions so they understand the types of news they might hear. Those taking part have to agree that they are willing to accept any emotional angst that comes with the findings. Students are provided access to genetic counseling and psychiatric care after receiving their results in case they want to discuss the outcomes further. If students prefer not to study their own genes, they can use a public reference sequence instead.

I was surprised to read in the prior pages two of the first people to have their genomes sequenced and published chose to conceal a specific gene from everyone, themselves included. Double helix codiscoverer James Watson and one of my favorite writers, Steven Pinker, apparently both chose not to learn about their apolipoprotein E genes, which might indicate a proclivity for Alzheimer’s disease. I can definitely understand how learning such a thing could be stressful, and I respect their decisions to not want to deal with it. At the same time, I know information is power, and there are many reasons the knowledge would be valuable. It would of course contribute to our further understanding of Alzheimer’s. It could of course result in relief if the results were favorable. Perhaps most importantly for individuals, knowledge of a possibly serious health problem could allow for better life planning. We should all be living every day like it is our last so we have no complaints when suddenly greeted by the Reaper. But we are weak, and anything that can help us focus on what is truly important is probably a good thing.

If those thought giants would find some information too scary to be known, of course it’s reasonable to expect others would have similar issues. I thought it was interesting the Stanford course seems to make such preparations for the students to handle the results when they are going through 23andMe, and the student presumably would get any of the warnings 23andMe deemed prudent for their public product. I wouldn’t think students at a prestigious university would need more emotional preparation than the general public, but I know schools also are sensitive to litigation and other threats, so caution is fine.

I am curious how many students might have had adverse reactions to learning about themselves. It seemed the warnings were more about the results themselves and less about the privacy concerns, so I can’t directly compare young people’s inclination to make data public and their possible sensitivity to finding out the information in the first place. They are separate issues, but definitely overlap, especially when it comes to the prospect your horrible health indicators might also become public, multiplying any emotional consequences.

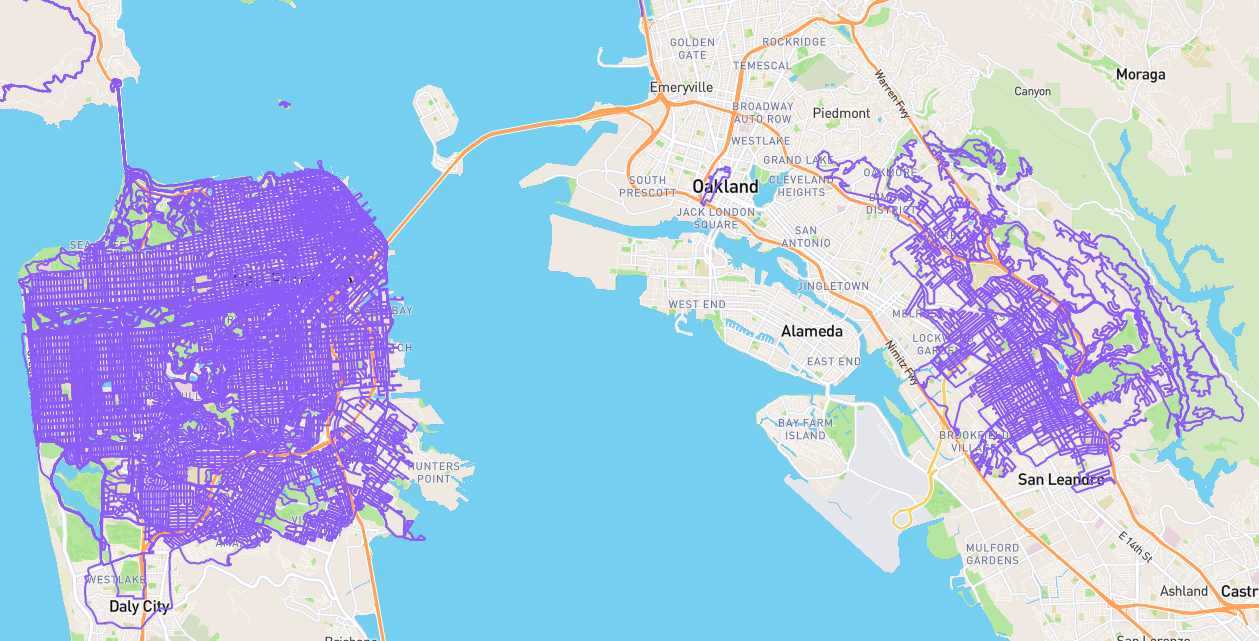

As for my results, I didn’t find anything too disappointing, though I must admit I was hoping to discover I was genetically resistant to the HIV virus. The vast majority of what my genome says about me is still unknown, so perhaps there is worse news coming. But still, similar to my attitude to getting sequenced once I learned how easy it was through 23andMe, I immediately signed up for the Personal Genome Project once I learned about it. I applied after they had exhausted the current funding, so I won’t be getting fully sequenced any time soon, but I was able to contribute the data available to me from 23andMe. I’m not sure if this raw data includes anything about the vast expanses of our “noncoding” DNA that we previously thought was purposeless, but whatever it includes, it is now public. And I clearly am not concerned about it becoming identified with my name and other information.

Reading now about all the possible emotional distress, I’m wondering what it is about me that makes me just not care. To an extent, I think I have being gay to thank. I have experience living with a secret, overcoming the fear of being found out, and finally embracing who I am with love and gratitude and humble acknowledgement nobody owes me anything, including life itself. Every moment I am given is one more moment to prove I am worth the fuel to keep me alive.

Especially as a sexually active gay, I and people close to me have had our share of HIV scares, and I know quite a few people who have embraced having become HIV positive. I’ve given a lot of thought to what I would do if I got HIV, and how I would feel about it. Of course I want to stay negative, and I started taking Gilead’s Truvada as PrEP around Christmas 2012 to protect myself. But I’ve also accepted I could get HIV, and I know I have to make my life meaningful either way.

While we haven’t yet found a cure, which is disappointing considering the level of investment in the cause for several decades now, the prognosis for a newly HIV diagnosed patient had gotten quite good. Most people can expect to live a nearly normal life and a nearly normal number of years. The stigma is still there, but things are getting better quickly. PrEP makes it possible for HIV negative people to embrace our brothers with extraordinary confidence.

Perhaps it is this story of HIV, which is still one of the biggest health issues worldwide, that made me better prepared for possible negative indicators found in my DNA. If this thing that is the worst thing is not that bad, what am I so afraid of? I like to think I’d still be fearless even if HIV weren’t a thing, and maybe it’s not really been instrumental in shaping my thinking. But acknowledging this possibility and that I really have no way to know for sure what even is going on in my mind humbles me to the whole life experience. What will come will come, and I’ll do the best I can.