ADHD research

Instead of catching up on my photos today, I’ll start gathering some research here regarding ADHD and medications. This isn’t intended to be a cohesive narrative, but a brainstorming work space. It’s public in case it might be of use to someone.

Literature notes

Stimulant medications for ADHD improve memory of emotional stimuli in ADHD-diagnosed college students

Overview of ADHD from the article

Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder is a developmental disorder characterized by three main symptoms: inattention, hyperactivity, and impulsivity. Although more than 5 million children have been diagnosed with ADHD in the United States alone, it is not only a childhood disorder; approximately 4.5% of the adult population may also meet the diagnostic criteria for this condition (Advokat, 2010; Advokat and Vinci, 2012). The affected adult population exhibits a variety of impairments, such as more marital and relationship problems, poor job performance, and lower socioeconomic status than the normal population (Biederman et al., 2006).

Many adults with ADHD are prescribed the same stimulant medications used to treat children with the disorder. The two main categories of stimulant drugs approved for the treatment of ADHD are amphetamine and methylphenidate. Amphetamine, marketed in formulations such as Vyvanse and Adderall, causes the release of catecholamines (primarily dopamine) from nerve terminals, and also blocks reuptake, whereas methylphenidate, such as Ritalin and Concerta, mainly blocks reuptake (Advokat and Vinci, 2012; Smith and Farah, 2011).

In spite of the well-established therapeutic benefit of stimulant drugs, several reviews of ADHD diagnosed children show that long-term stimulant use does not improve academic performance (Advokat, 2009). This is consistent with evidence that adults with ADHD are also less likely to reach predicted education levels, independent of medication use (Biederman et al., 2008). Among adults, college students with or without an ADHD diagnosis are especially likely to take stimulants to enhance memory, organization, and alertness (Advokat and Vinci, 2012). However, we have found that, regardless of stimulant use, the academic performance of ADHD-diagnosed undergraduates is still statistically worse than that of their non-ADHD cohort ([Advokat et al., 2011][advokat 2011]). Considering the well-documented stimulant-induced improvement in attention, it is surprising that these drugs do not produce better academic outcomes.

Authors’ conclusions

The researchers assume (I haven’t traced this claim) students with ADHD do worse than other students, regardless of drug use. (On the face, this seems rather expected: a disease puts you at a disadvantage, even if you take medication that aims to bring you closer to normal.) The researchers therefore wanted to test if drugs improve cognitive performance at all. This study apparently shows the drugs do improve performance for ADHD students. The researchers conclude the worse academic performance shown earlier must be due to:

- students not taking the medications on optimal schedules

- a non-cognitive factor unaffected by or made worse by drugs (Bidwell et al., 2011; Swanson et al., 2011)

Problems

Participant selection

- Participants self selected by responding to campus fliers and an “extra credit system”

- Participants chose for themselves which study group they wanted to participate in (acknowledged: )

- Having a prescription used as proxy for ADHD diagnosis confirmation

Procedure

- Perhaps medication affected the initial viewing session and the week later recall session differently

- ADHD participants without medication were presumably on medication up till the first session and between sessions

- Assumption all ADHD medications and doses have the same effects

My thoughts

Right away, I’m disinclined to put much stock in the research here, though as the first article I randomly chose to begin my research, I found the introduction and references helpful.

First of all, that the students were not randomly assigned to their groups opens a giant fricken can of worms, and pretty much eliminates any conclusions we can draw from this unless the effects are unmistakable and extremely, intuitively significant. Even then, I’d be cautious. The authors acknowledge this and yet seem confident in the results:

This was an unavoidable design weakness, in that we were not authorized to impose these conditions on our participants. However, this is not an uncommon experimental constraint when conducting naturalistic research. Although the choices appeared to be related to the participants’ respective academic schedules, rather than any systematic confound, it is possible that this self-selection might have affected the outcome.

Second, the ADHD diagnosis and drug specifics seem very fuzzy to me. I don’t know if this might have been established by previous research, but we’re talking about two separate categories of drugs (amphetamine and methylphenidate) and apparently unknown doses (other than “doses were in the approved range”). In my anecdotal experience, it is possible for patients to largely select their own drugs and doses, and indeed even select their ADHD diagnosis, based on personal preferences and desire for enhancement, medically warranted or not. All these unknowns call for rigorous experimental conditions and numbers, and I don’t see it here. The study groups only had a dozen students, and that’s on top of the noted selection problems.

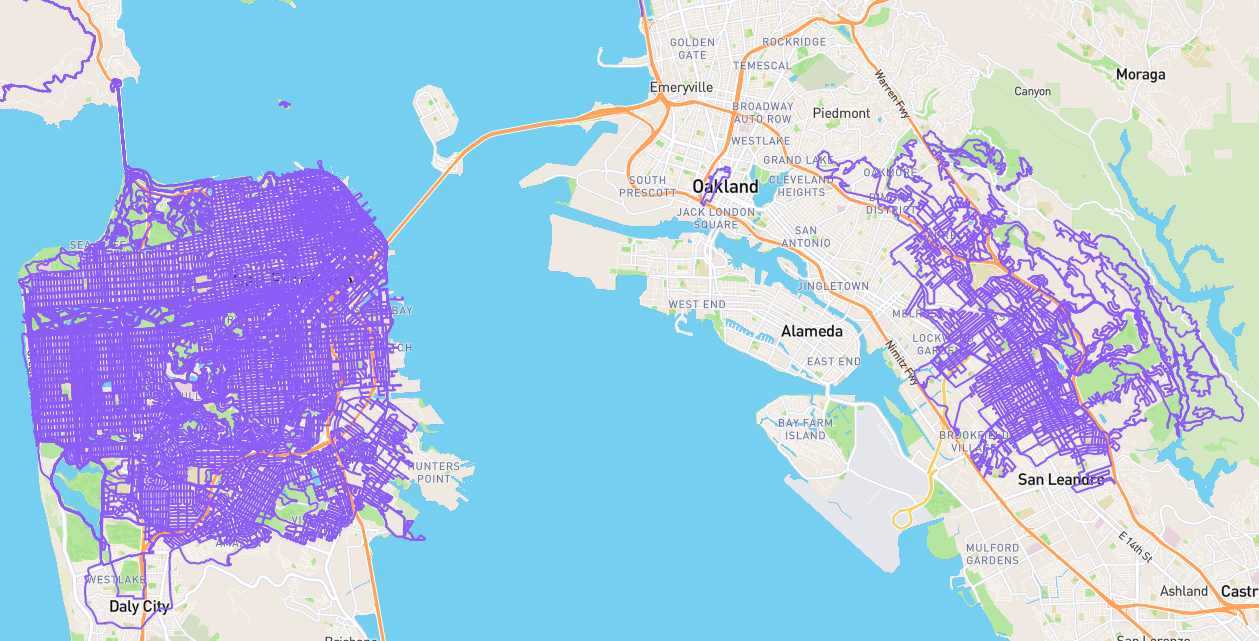

Third, it seems pertinent to know if the effects of the drug are uniform for all students or only apply to the ADHD students. From this study, I have no idea if ADHD has anything at all to do with the drug effects we’re attempting to measure. The results are summarized in this figure from the article:

The researchers acknowledge some of these issues:

- “the administration of stimulant drugs to nondiagnosed participants was not legally permissible”

- “it is possible that this self-selection might have affected the outcome” / “unavoidable design weakness”

- “Even with such a modest amount of data”

Well, I hope they can find a way to overcome these issues. Perhaps they have, and I just haven’t found the paper yet.

One interesting note, which I’ll have to research later, was this:

This perspective is supported by Izquierdo et al. (2008), who also showed that methylphenidate promoted recall at longer time intervals, and only in situations where performance was already impaired. Specifically, those studies found that subjects over 35–40 years old were significantly less likely to remember information they had received seven days before, relative to younger subjects. After methylphenidate, only older subjects showed improvement: their age-related memory deficit was reversed, and they remembered as much information as the younger subjects.

This seems to indicate taking ADHD medication might only get more important as we age, despite the current situation where most ADHD patients are apparently children and teenagers.

Tangents

I googled one of the researchers most frequently referenced in this article, Claire Advokat, and found this nice image of her:

I also found some reviews of her teaching. It’s pretty interesting to think of the authors of scientific papers as real people. I commonly research authors of books I enjoy, but haven’t much done so for authors of papers. But they are obviously people, and they have the added dimension that they are mostly all teachers, and you can read not just reviews of their works, but reviews of their teaching. And since their students are also humans with infinite differences, the reviews can be quite varied:

From http://www.universitytools.com/U/LSU/Fa05/Instructor/2909/ADVOKAT+C:

- Review #10: “Dr. Advokat was one of the best professors I’ve ever had. She’s friendly and truly enjoys teaching the course. …”

- Review #5: “I don’t know why people are saying she is a good teacher! She’s the worst I have had! …”

- Review #1: “She is a horrible teacher. …”

- Review #16: “The class was great; the professor could be very rude.”

From https://www.koofers.com/louisiana-state-university-lsu/instructors/advokat-319596/:

- PSYC 4035: DRUGS BRAIN BEHAVIOR

- Pros: Really interesting material covered in this class! Made studying the mounds of information bearable.

- Cons: Advokat is rude & a know it all. The exams cover a TON of information and are quite difficult. Advokat is pretty awful. She is very knowledgeable about the field, which she lets you know from day 1. She is very condescending throughout her lecture. And the tests are EXTREMELY detailed & tricky so prepare to study a lot & give yourself enough time to cover everything. Only psyc class I’ve ever gotten a B in.

Also, I enjoyed reading Citations in Scholarly Markdown by Martin Fenner (June 2013) in preparing to write some of these notes.